Modernity (from Descartes onwards) frames the universe as a great feat of engineering. All models and ideas we use to make sense of our world follow engineering logic and principles.

The cosmos, nature, our bodies are seen as predictable machines, following rules and linear processes. Mechanical and thus knowable. Study enough of the parts to fathom the whole. We might even consider the death of the whole a necessary sacrifice for the understanding of specific parts.

Within that worldview, change requires little more than redesigning, tinkering and implementing the new design so that the machine will run differently. Adjust some rules, reshape a cog or two, and the linear process will continue on a different course. The watchmaker analogy.

The lure of modernity lies in the promise to re-engineer nature or our bodies, to have them molded into a direction of our own choosing. Progress being little more than 'getting better at engineering it'.

This, of course, sets the old and traditional in opposition to it, as something that has not been retro-fitted yet. Hence it is seen as backwards (or downright stupid) and not keeping up with the times.

The rise of the ecological

Yet, when I look at our current period, it feels like some of us are slowly escaping from this worldview. They seem to shift from a model fit for engineering to a model that is much more ecological.

As a culture, some of us are reflecting upon the continual retrofitting that we have done and realise we weren’t retrofitting these machines in a sterile laboratory. We were actually intervening in an awe-inducing bountiful garden.

With that reflection, the realisation dawns that none of the machines and processes we intervened in stood in a vacuum. By course-correcting processes and machines, we have generated 2nd, 3rd, even 4th order effects that none foresaw when they started re-designing the world. Or to put it in engineering terms: these consequences were ‘out of scope’.

But here lies a big pitfall. In a sense, one can never fully know the extent of transformation. To be transformed not only means the machine itself gets reshaped. It means the world around the machine has to reshape as well, in order to accommodate the new form of the machine.

To think you can predict what you would be transforming into, as if this was a linear process one would just go through, is to fundamentally misunderstand what transformation entails.

The great unveiling

Today, we live in Apocalyptic times. Not in the 'end of the world' sense, but in the ‘end of the worldview' sense.

The apocalypse (from Greek ἀποκάλυψις; uncovering/unveiling) removes the veil that covered the shortcomings of the engineer. The trade-offs are coming into view.

I don't want to go into too much details on where our worldview got itself stuck.

I'd much rather leave you with the great Louise Perry to give you a reflection on some trade-offs that have taken place within the domain of motherhood alone.

As an early 30s father of four young children (one of the main reasons why I have been having a hard time writing more often on this Substack), I can attest to these observations from my own experience.

My wife and I often feel like a Generation Zero; trying to relearn, revalue and figure out the most basic and natural things. Little praxis of use has been handed down through the last three generations.

Figuring out things yourself that were normal 5 generations ago takes lots of energy. We’ve been confronted many times over with how much of the prerequisites for fruitful parenting have been dismantled, as Louise points out.

In a sense, we have lost the ecosystem that surrounded motherhood (and fatherhood). These roles were reduced to the mechanical notion of sex leading to fertilisation and eventually children. Beings that severely impacted the economic output of the individual parent, so we had to start thinking about how to raise them without having the parents restricted too much.

Childraising and its consequences became a problem for engineers to solve.

I learned first-hand that I can’t engineer my kids nor my family. Parenting and marriage are much more akin to gardening. Not one kid is the same, either. They all need different things.

I can facilitate; space, time, good nutrients, and the right amount of water. I may pick the soil, but I can not control every influence in the garden. I can provide shade, I can not stop rain, prevent storms or make sure the sun shines.

Nor can I regulate and manipulate the people around me as if they were objects or machines. I might try, but it will only cause me to end up with a barren patch of dirt. Hardly to be called a garden.

How to become initiated as a gardener?

We're at the apocalypse of the modern worldview and have not yet figured out how to relate to a new ecological worldview (or is it old, very old? Ancient, perhaps).

We haven't been properly initiated. We're adjusting slowly to behold the world with new eyes. Perhaps even a new soul.

Entering the new will require a true metanoia (again, from Greek: μετάνοια, to go beyond one's thinking/perception, so that one has a new perspective on the world and one's place in it). These days, it is often translated as Repentence; to confront your sins and regret them, in order to get on the right side of god’s grace.

Its original meaning refers to a radical change of mind or heart. A conversion and initiation into a new way of living/being. Sure, you might regret the old you in that process, but it’s not a prerequisite for it.

A true metanoia

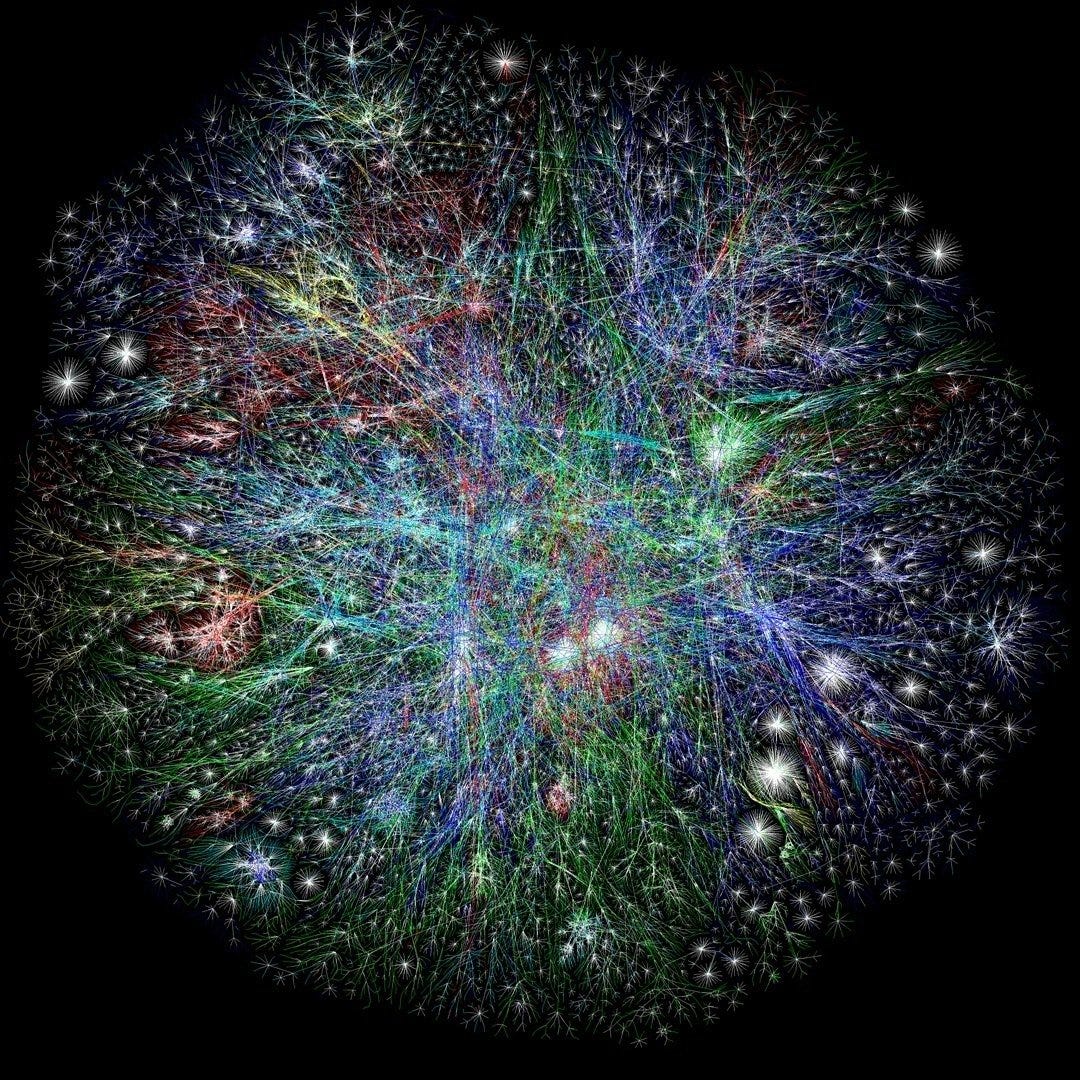

It's hard to restructure our current worldview to follow ecological logic. The engineering logic lacks ways to integrate some of the core principles of an ecological framework. It can not cope with the world as a rhizomatic network of processes.

Undoubtedly, this will lead to a sense of aporia; the sense that all current models fail to grasp the world around us. Such an experience can be the cause of strong anxiety.

Individual human cognition is constrained in how much data it can compute. Our actions are energetic impulses impacting vast networks, reverberating into consequences long after we are capable of calculating them.

Add to that the fact that engineers often think in terms of one-direction manufacturing flows. Ecological models always have to account for output feeding back into the flow, transforming it as the process goes along. The flow has to restructure after every run, because the output feeds into the new input, and the output might impact several of the variables surrounding the process.

Leaning into the rhizomatic will eventually upend the modernist self-image. As conscious organisms we emerge out of and are upheld by a proverbial mycelium network of these processes. We aren’t self made. We arise out of ever fluctuating processes and are cupped in the hands of an ecosystem that we do not fully know.

It took generations for some of the 3rd and 4th order effects of ‘progress’ to really show up clearly. Even now we don’t fully understand if these effects were predestined to show up, or that we never took into account how output would feedback into our progressive push, or just didn’t install a proper quality check because our conveyor belt thinking thought that it would always be the same output.

As Louise's cassava analogy points out; human do things that - from an engineer's perspective - seem inefficient, redundant, wasteful. So the engineer tries to cut these processes off. It doesn’t see the need for it. It values efficiency. If it can not explain the need, it needs to go.

But in order to explain, one first needs to have understanding. If you don’t have the means to understand something, you can not explain it. It appears now that much of our redundancy is a way to regulate output. To make sure that a process doesn’t just run off on its own, spewing output, poisoning the well.

Just like in the cassave analogy; skip one step and the lingering cyanide will poison you slowly. So it goes for the proverbial mycelium network surrounding us. Remove the ‘redundant’ things, and the network dies off. Without this proverbial mycelium network, the necessities for a life well-lived, become more and more scarce. Eventually that what emerges from the network fails to become strong and durable.

The failure to engineer paradise

Much of what we use to structure our model for the world builds on engineering principles. The linearity, the eschatological idea that one day we'll know the world fully and will transform it to be perfect.

The tempting promise to achieve what god failed to deliver; paradise. You will realise that the engineer fights for its worldview; requesting ever more calculation, more bureaucracy, more control to deliver on what it originally promised. His construct will become topheavy, even if the fractures are already making it very unstable. It might even collapse completely.

The irony is, paradise is already here. All around us. The problem is that it doesn't follow engineering principles. Paradise follows ecological principles. We call it a 'garden' for a reason.

The cherubim with the flaming sword (Gen 3:24) won't let the engineer with its impure reason through. The Tree of Life is not accessible for them.

The spirit of the engineer won't give up without a fight. It is fighting to the death, which is most visible in the current climate/ecology discours. The old is doing its very best to suffocate the emerging new, trying to requisite and repurpose the ecological discours to its own logic.

By pruning the ecological view down to the mechanical, sterile and predictable engineering model, it tries to survive by subjecting the ecological to the Machine. It attempts to monetising nature in its last effort to stay in control.

It won't allow itself to collapse and dissolve into an ecological worldview. It wants to become topheavy. Mind you that if it collapses then, this might pull us all asunder.

In order to overcome this civilisational bottleneck, the need for a cultural metanoia into a worldview following ecological logic and principles becomes ever more and more pertinent.